The Pines and the Fight Against AIDS

Commemorating World AIDS Day, December 1st

By Virun Rampersad, November 2025

World AIDS Day is a good time to look back on how the LGBTQ+ community took on a seemingly impossible challenge – as well as powerful, hate-filled resistance -- and transformed a once fatal disease into a manageable health condition. The Pines community played a lead role in this effort that transformed medical research and drug development practices, benefitting millions of people around the world and paving the way for the sexual freedoms we enjoy today. This story is an important reminder that once we commit ourselves, there are virtually no limits to what we can do.

The Pines was Ground Zero for both the start of the AIDS epidemic and the world’s response to it. In the early 1980s the disease struck the community suddenly and with devastating force. Within a few short years, hundreds had died and many more were infected. Houses sat empty, the once-vibrant crowds of men on the boardwalks thinned, and skeletal figures, sometimes with visible Kaposi Sarcoma lesions, began to appear. Each day brought the same questions: Who’s sick now? Who’s gone?

The impact of the plague was far-reaching. People with AIDS often lost their jobs (anti-gay discrimination was openly practiced in the 1980s) and many were shunned by their families, leaving them at risk of homelessness and without access to food or medical care. In the earliest years especially little was known about the virus or how it spread, fueling misinformation, a rise in homophobia, and the ostracization of gay people. A cruel mid-1980s joke captured the moment’s ugliness:

“Do you know what GAY stands for? Got AIDS Yet?”

Not surprisingly, many people fled the Pines. Their departures, combined with the forced sale of homes by sick or deceased residents, depressed property values and depleted financial resources.

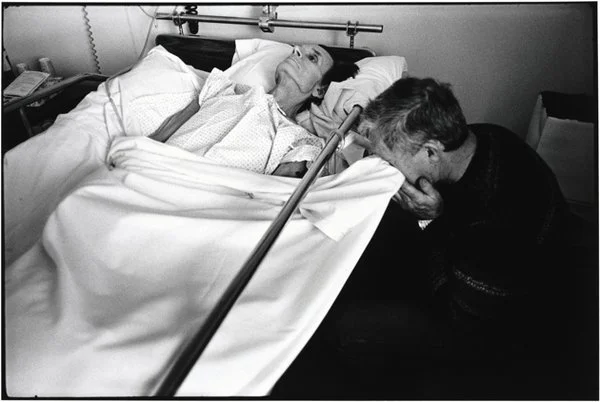

At a time when there was virtually no government or civic support for people with AIDS, the meaning of ‘community’ was suddenly and profoundly reframed. In the Pines and across the country, friends became caregivers overnight, building informal networks to keep the sick housed, fed, and connected to medical care.

This work was emotionally and physically demanding—AIDS often brought gruesome, painful, and messy deaths—and many who stepped forward did so knowing the same fate likely awaited them. These quiet caregivers were among the true heroes of the crisis.

AIDS Victim in hospice. Photo credit: David Kirby

With their backs to the wall, gay people fought back. The first act for many was coming out—AIDS made life in the closet nearly impossible. The second was organizing. That work happened at every level: within chosen families, within communities, and eventually at city and state levels. The Pines was part of all of it. Friends cared for sick housemates on the island and in the city, and both residents and businesses rallied to raise funds and provide direct help.

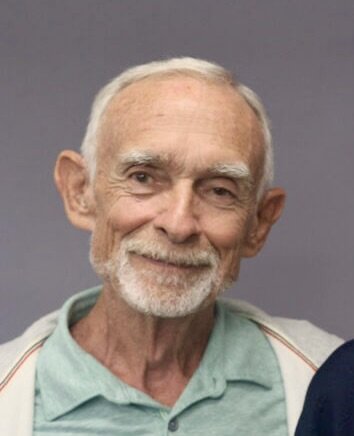

Among the most notable was The Pines Liquor Shop. Owned by Jack and Rita Lichtenstein, it mobilized its delivery team—including today’s owners, Steve and Chris Nicosia—to run errands, provide transportation, carry IV bags, and help sick residents with basic tasks.

Rita and Jack Lichtenstein. Photo courtesy of The Pines Liquor Shop

At a time when many would have turned away, the Nicosia boys could be seen ferrying people with AIDS around the Pines on their delivery vehicles (there was no Mobility Cart in those days) treating all with courtesy and respect—a stark contrast to the reception they often got in the city where being spat upon or denied service was far too regular an occurrence.

Steve and Chris Nicosia with honor from SAGE for their outstanding service to the Pines. Photo courtesy of The Pines Liquor Shop.

One of the most visible and impactful responses to the crisis, Gay Men’s Health Crisis (GMHC), had deep roots in the Pines. Founder Larry Kramer was a regular visitor, and co-founder Paul Popham had a home here. Shortly after GMHC’s founding, Jim Pepper risked his Wall Street career to join its board, and (future) Pines resident Eric Sawyer helped found and lead ACT UP, bringing new urgency and political pressure to the fight.

Jim Pepper. Photo courtesy of Bill Mattle.

The Pines became active in AIDS fundraising, hosting events like The Morning Party to support GMHC and other AIDS organizations like the Foundation for AIDS Research (AmfAR).

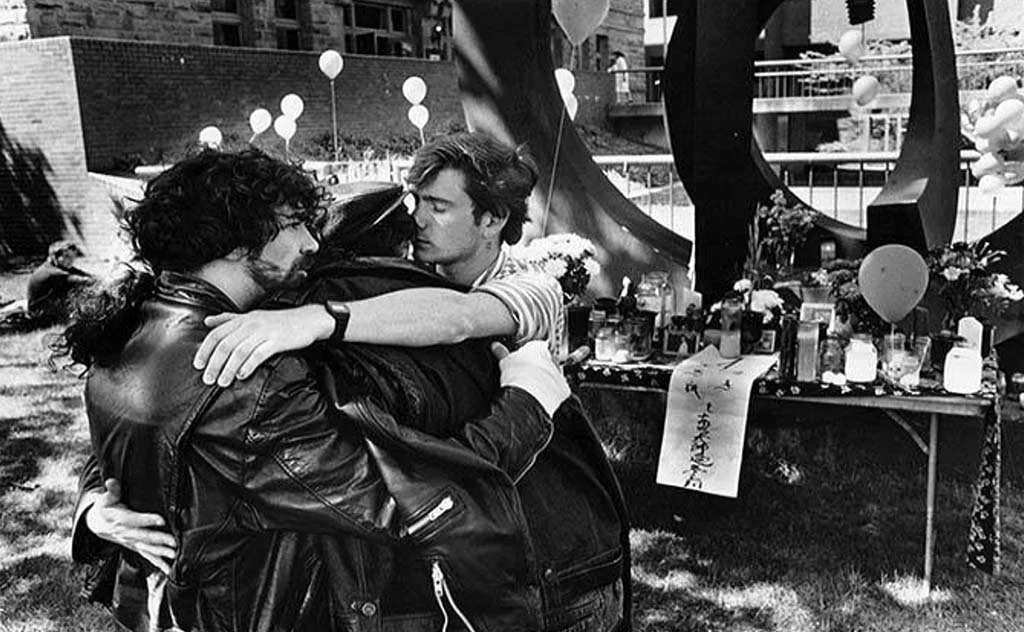

What characterized much of the Pines’ response to the crisis was its blend of community, joy, and activism. Its organizers sensed that fear and anger alone would not be enough, and the fight must also tap into emotions of fun, optimism and celebration if it were to have the necessary staying power to succeed. As such, many fundraisers celebrated life and freedom, and were rooted in a belief that the community would endure, and its best days were still ahead. Longtime residents—Ward Auerbach, Jay Pagano, Steve Foster, Hal Rubenstein, Scott Bromley, and others—all of whom lost many loved ones, recall that even at the darkest moments, the Pines remained a place of solace, comfort, hope, and inspiration.

As Scott Bromley put it:

“As hard as those days were, the Pines, with its natural beauty, closeness to nature and that special magic, helped me keep the faith that we would get through this, even though I didn’t know how.”

Scott Bromley. Photo courtesy of Bromley Caldari

The determination and unwavering commitment of leaders around the world to battle the crisis was nothing short of heroic, especially given the fierce opposition they faced. Unlike COVID-19, where there was near-universal support for finding a cure, many actively opposed the fight against AIDS.

Senator Jesse Helms described AIDS as the result of “unnatural, deliberate, disgusting, revolting conduct” and fought to block funding for research. (In protest, ACT UP famously draped a giant condom over his house.) William F. Buckley Jr. argued that people with AIDS should be tattooed. Pat Buchanan called AIDS “nature’s revenge on homosexuals.” Rev. Jerry Falwell declared it “God’s punishment.” Even New York Mayor Ed Koch, widely believed to be gay himself, resisted early calls for meaningful action.

Senator Jesse Helms. Photo courtesy of US Senate Office of Jesse Helms.

Opposition did not come solely from the political right. In the early years, there was also resistance within the gay community—including in the Pines and Cherry Grove. Some saw AIDS as an attack on hard-won sexual freedoms and resented suggestions that the beaches, bars, clubs, and bathhouses that defined gay liberation had become dangerous. Others, fearing stigma and economic damage, urged the media to downplay the threat. Even safe-sex education initially met resistance.

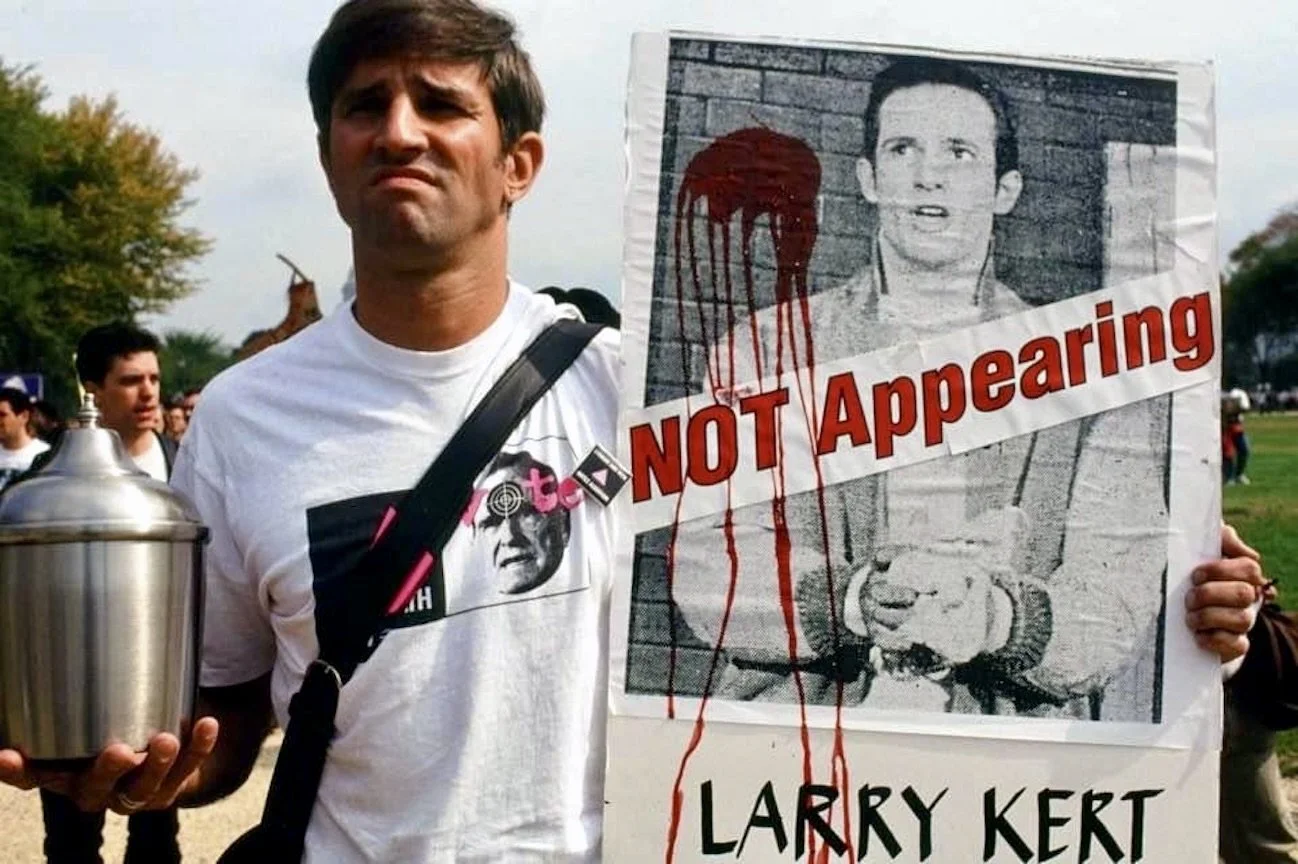

This was the climate the early AIDS leaders confronted. Their achievements—from mobilizing people, to fighting the idea that people with AIDS were not victims, to forcing government and private-sector engagement, to reshaping the way the medical profession approached drug development, and ultimately to the creation of lifesaving antiretroviral therapy in the mid-1990s—stand as one of the most remarkable activism-driven transformations in modern history.

What began with Larry Kramer distributing mimeographed flyers in the Pines Harbor, and continued with Eric Sawyer and others marching, protesting, and even scattering the ashes of loved ones on the White House lawn, grew into a global movement that changed the world.

Eric Sawyer at White House Protest. Photo courtesy of Eric Sawyer.

It not only created lifesaving AIDS drugs but fundamentally modernized medical research itself. The changes it brought accelerated drug development, reshaped clinical trials, reframed health ethics, and established patient advocacy as a core part of scientific practice. In this way, their work advanced progress in fighting many diseases, not just AIDS, and benefitted millions of people around the world.

Men Embracing at World AIDS Day 1988. Photo credit: Historylink.org

The simple truth is that the work of the early AIDS activists—many of whom had roots in the Pines—improved lives globally in countless ways. Marking World AIDS Day is therefore not only a remembrance of those lost and a tribute to the heroism of ordinary people, it is also a celebration of what we can accomplish when we harness our collective power. At a time when the LGBTQ+ community is once again under siege, it is a message worth remembering.