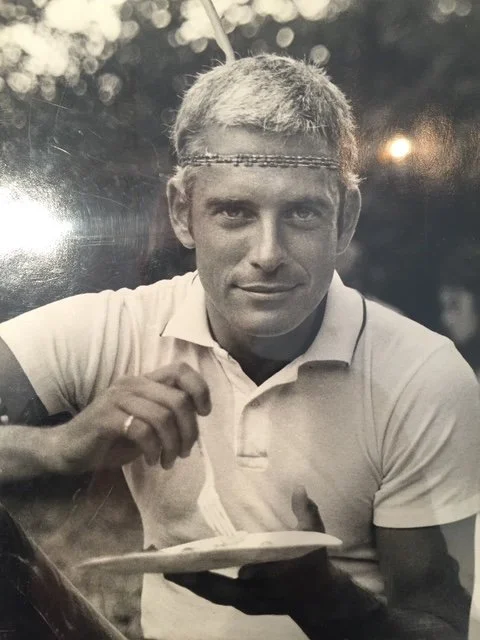

Pines Profile - Scott Bromley (b. 1939)

An Architect of the Community

By Robert Bonanno and Virun Rampersad, July 2025

Over the course of more than six decades, R. Scott Bromley has built a remarkable legacy in Fire Island and New York City. His life’s work has exemplified architectural brilliance, cultural stewardship and profound community care in the places he calls home.

Born in 1939, Scott Bromley first came to Fire Island in 1964 when he visited Cherry Grove with his then boyfriend. He was, in his own words, “just a green kid from Canada.” He’d recently graduated from McGill University in Montreal and he arrived in New York determined to build a career as an architect.

Although he had a good time, Bromley did not feel a strong bond with the Grove. In fact, he did not return to Fire Island until 1968 when his friend, the actor Remak Ramsay, invited him out, this time to the Pines. It was love at first sight.

Right away young Bromley decided the Pines was the place he wanted to be, and so he took a job as a houseboy in a house on Ozone. Here, he was simply required to prepare three meals a day. The job was a great fit with his needs and his wallet and he went on do it for several years.

It’s worth noting, that in the 1960s the Pines was a long way from the glamorous resort community it is today.

In the early sixties, says Bromley, most dwellings were essentially beach shacks on small plots, creating a ‘back-to-basics’ haven from the urban towers of Manhattan. Few people had phone lines, a few more had washing machines.

“There was electricity and running water but otherwise, it was frontier-ville,” he laughs. “Architecturally, there was nothing outstanding; they had mostly pitched roofs, and there were very few two-story houses, usually just one or two bedrooms and an open kitchen, living and dining space. And a lot of deck. It was the outdoor living that was really interesting—you came here in the summer months and God help you if it rained. You’d be crowded inside, playing Canasta or charades.”

Around that time, the legendary architect Horace Gifford was just becoming established on Fire Island. His first works were in Seaview and Cherry Grove, but it was in the Pines where he made his biggest mark. His aesthetic, characterized by cedar-clad structures, dramatic rooflines, and sunlight-maximizing layouts, came to define the Fire Island modernist vernacular. In the 60s and 70s, Gifford would design over 60 houses on Fire Island, many of them in the Pines. His works inspired Bromley, who over time also embraced sustainable wood-and-glass modernism to complement the landscape.

“He was the ruling guy in terms of Fire Island modernism,” says Bromley, “And he was my hero in beach architecture. He lived behind me, and I knew him well. I did once sneak into one of his houses, which belonged to Calvin Klein, and found a set of rolled up drawings—and the details were incredible. He was a great planner and architect, and I found a lot of stuff I was doing was in sync with him.”

Although he would later go on to be one of its preeminent architects, Bromley’s first house was not in the Pines or even Fire Island. Rather it was in East Hampton, Long Island, built in 1972.

Indeed, Bromely went on to do another major house in East Hampton in 1972, 4 Baiting Hollow Road, a 4,000 square foot home that was featured in both Curbed and New York Magazine.

In his early years, Bromley focused on building his career in New York, preferring to leave Fire Island for relaxation. He set up his own business in 1974 and hired his future business partner, Robin Jacobson in 1975.

Despite his reluctance, Bromley slowly began doing work in the Pines, beginning with a small job for his neighbor, who was having her house built by a builder without an architect. Bromley redrew the house plans on graph paper so they could have an extra bedroom, an open-plan kitchen and a dining room in the same building envelope the contractor had signed off. His neighbors were delighted and Bromley was rewarded with a case of Cristal for five consecutive years.

As Bromley noted, it was a good start and led to other small jobs across the island.

“It escalated from there, with people asking me to do their bathroom, or their deck, or design some simple furniture,” he says. “I got involved. I’m not sure that I loved working where I vacationed, but I love what I do….”’

It was in these jobs that Pines homeowners got a glimpse of Bromley’s talent. One homeowner asked him to redesign the single bathroom in her house on Atlantic Walk so her five tenants could be in there at the same time and not get in each other’s way. Scott’s successful redesign was soon the Talk of Tea amongst the homeowners.

These early Pines successes, however, were nothing in comparison with what was about to happen in New York. In 1977 Bromley had two major break throughs. First was designing a two story retail store called Arbitare, which was a huge success that helped propel him into the limelight. The opening party also helped launch another star, the caterer - at that time the little known, Martha Stewart.

The second success came with the glitz of the 1970s, when Bromley partnered with Ron Doud to design the interior of the famed nightclub, Studio 54. It took off with a bang and so did his career.

As Bromley put it “When we designed Studio 54 in 1977, all hell broke loose!”

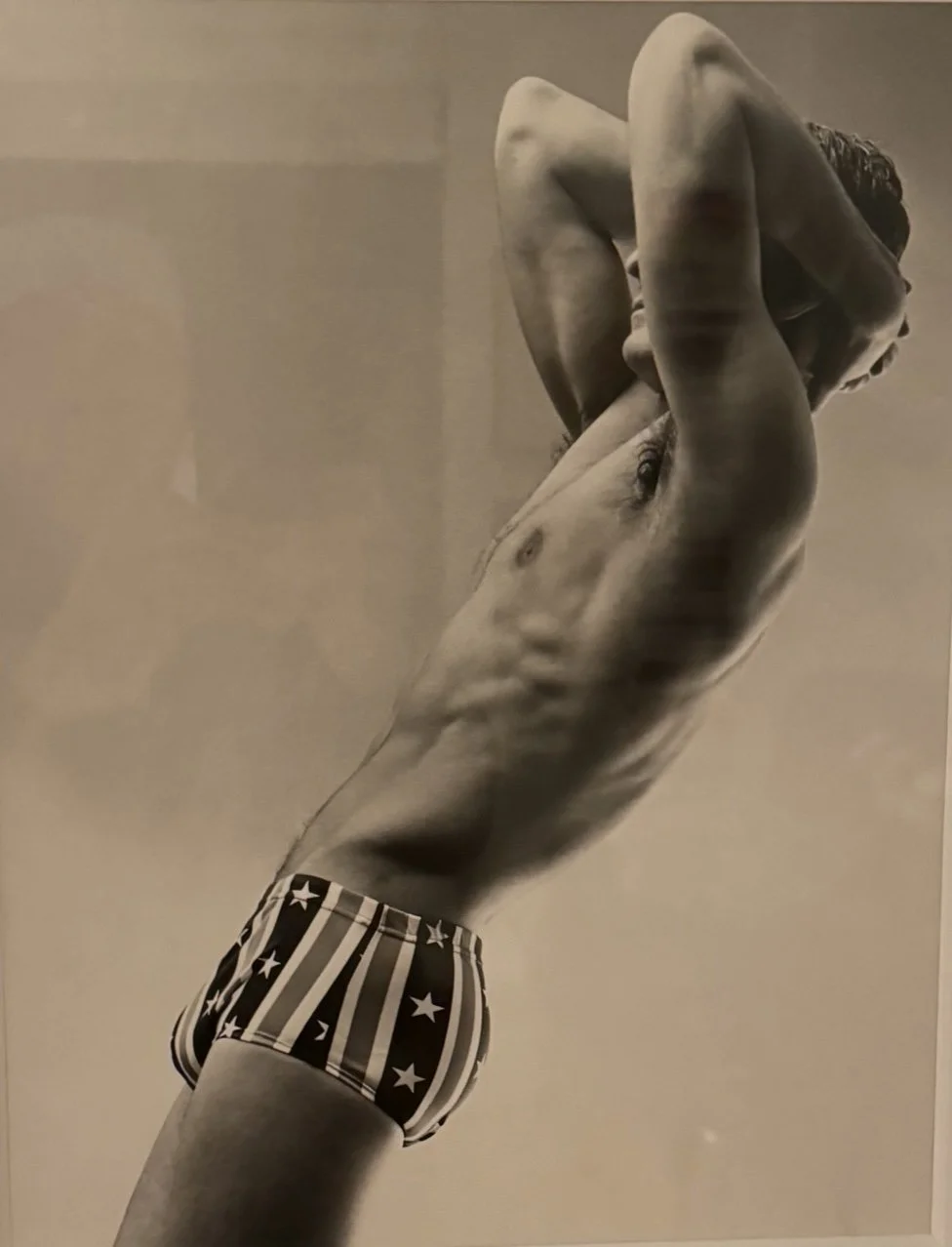

As documented by the photographer Tom Bianchi in his 1975 to 1983 polaroids, the Pines at this time was going through a period of liberation, camaraderie, and pleasure, carried out against a backdrop of white sand, winding boardwalks, and eternally blue skies.

It began to attract an increasingly wealthy and talented vacation community that included many in fashion and architecture, such as Calvin Klein and Fern Mallis (below), the creator of New York Fashion Week.

Demand for new houses with modern amenities surged, leading to the development of new homes from architects like Gifford, featuring low-tech wood-and glass houses that sat lightly among the protected dunes of the island, embedded in nature.

In many ways, Gifford’s houses were the antithesis of the suburban ideal: no cars, no carefully maintained lawns, no fences, just meandering paths that took you from the boardwalk to the front door. Gifford, who often talked his wealthy clients into building houses with a smaller footprint, is quoted by his biographer, Christopher Rawlins, as saying, “Someday we will learn to live with nature, instead of living on nature.

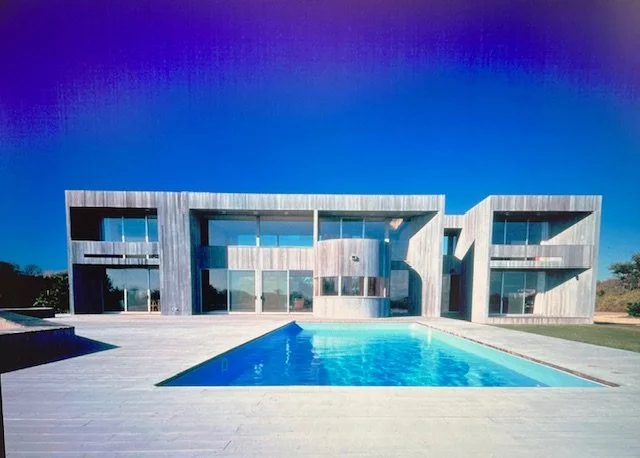

Inspired by Gifford, Bromley developed his own signature style that was more in keeping with the lavish ambitions of the community. Using light, and natural materials he began to design houses with geometric contours, cedar siding, glass walls, and sparkling pools. He embraced ocean light and dune landscapes. and created interiors favoring warm wood, neutral palettes, and fluid spatial planning, rejecting overly elaborate ornamentation in favor of functional elegance rooted in the ecology of Fire Island and respect for nature.

This era, sometimes called the “Disco Era” has often been called the heyday of the Pines. It had just about everything. There were cocktail parties, theme parties, Tea and late night dancing. There were elegant dinner parties, orgies and even athletic competitions between the Pines and Cherry Grove.

The freedoms post Stonewall were like never before and gay men from across the country flocked to enjoy the merriment and debauchery the Pines had to offer.

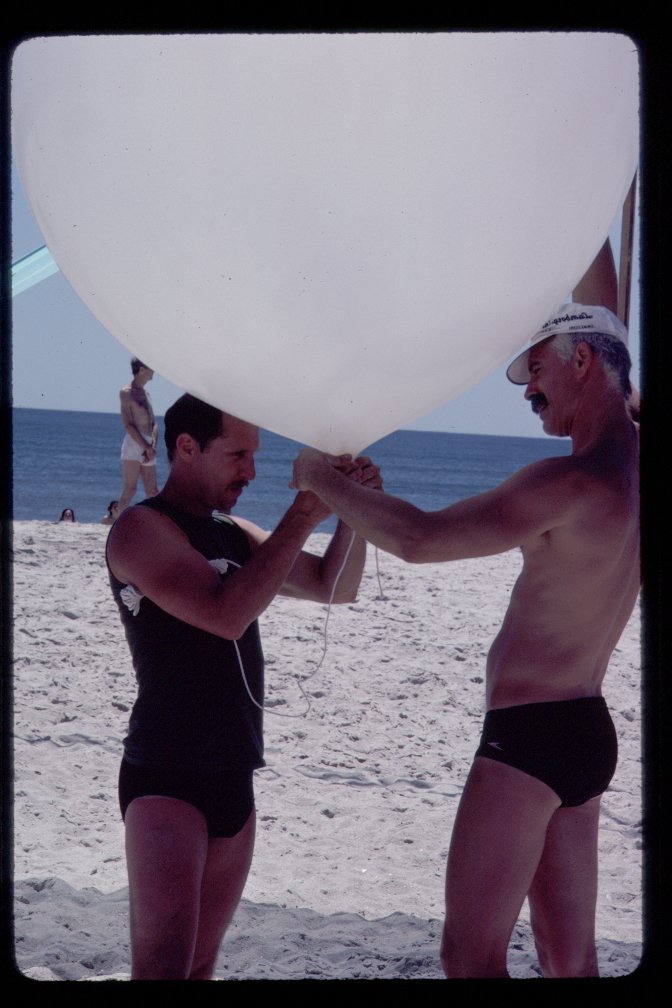

The period also marked the genesis of the circuit party. In 1979, working with Ron Martin and Fern Mallis, Bromley and his partner, Robin Jacobsen set about an ambitious task to create a party on the beach in the Pines. This had never been done before. With the vagaries of the elements, plus the challenges of beach construction, there were those who doubted it could be done. However, through his brilliant design and support from people across the Pines, they created what was widely described as “magic”. Simply called “Beach,” the party attracted 2,000 people, showcased the rising talent of the then-16-year-old Canadian chanteuse France Jolie and raised enough money to buy a new firetruck for the community. It became the grandfather of all-night dance events nationwide. It also cemented the Bromely’s place in community lore.

That year Bromley started hosting an annual summer party at his house called “Margaritas from Hell”—a tradition he upholds to this day: “People were coming along, and saying they’d love me to do their houses. It was all word of mouth, because obviously there wasn’t the internet at that point.”

In 1980, Scott moved into a Gifford house on eastern side of the Pines. This move not only signifies his admiration for Gifford’s style but also laid the foundation for his later adaptations and designs in the Pines, bringing Gifford’s beach modernism forward into the subsequent decades.

It was the happiest of times and everyone was brimming with excitement about the future.

The very next year the AIDS epidemic broke out.

It ravaged the Pines with blinding speed. Almost overnight entire groups of housemates were wiped out. Bromley himself lost a boyfriend who died in his arms.

“Half the town disappeared,” he says, “Initially, it was one funeral every other week, then it became one per week and then several per week. It was sheer devastation.”

Bromley began writing the names of people he knew closely who had died in a journal, one each day, starting on the first day of 1980. Halfway through the year, he had filled the pages to May - around 120 people - among them his original practice partner, Robin Jacobsen and his mentor Horace Gifford.

No one who lived through the AIDS epidemic was untouched. Bromley’s response was deeply integrated into who he is, not just as an architect, but as a human being rooted in community. To his surprise, he never got sick himself and volunteered to be a part of a study at New York University to understand what was it that had helped him stay healthy. He honored the dead, supported the living, and helped build places where both could find meaning. These included the first two offices for Gay Men’s Health Crisis and Larry Kramer’s apartment, all of which were done pro bono. This was no small sacrifice as it was a lean time in his business, but for Bromley it was a way to do his part. Beyond this, most of his time was spent raising funds and awareness to fight the plague. Through all this death and devastation, Bromley’s connections to the Pines grew, as he found solace in the beauty and calm of the environment.

As the community began to right itself in the early 90s, people began to look to the future with more confidence. Having established a reputation for excellence and elegance that blended perfectly with the natural surroundings of the Pines, Bromley with his new partner Jerry Caldari became the go-to architect to design the next generation of houses in the Pines. Over the next two decades, they would go on to renovate and design some of the most iconic houses in the Pines.

One of the most notable works was a transformative renovation of a 1960s A‑frame home on Great South Bay, which they completed around 2013. It was a challenge as neither the height nor the central spiral staircase of the old beach rental were legitimate from a building permit perspective.

“It was interesting, because the roof is also the walls,” says Bromley. “You bumped your head on the staircase, which was right in the middle of the view. In a traditional house they’re not considered the main means of egress [for safety reasons]. Three-level buildings aren’t allowed in the Pines either, but this was built so long ago it was just grandfathered in.”

The firm bent the rules a little further and installed bay windows that extend slightly beyond the building envelope, adding an extra two feet of space on each side. This allowed them to build a sculptural, “real” staircase. “We had to be careful, because each floor gets smaller the higher you get we had to be very clever about hiding things in the triangle.”

The original steel spiral staircase, which bisected and darkened the interior, was replaced with a sculptural, light‑filled stair integrated into large bay‑window extensions. Bedrooms were reduced from four to two to open up the space. This renovation immediately became emblematic of modern Pines architecture.

The Ocean View Complex in the west of the Pines was another success.

A sprawling compound of interconnected structures that includes a main house, guest house (Albert House), gym, dining pavilion, and pool cabana, all linked via boardwalks through the dunes. It functions as a mini-village retreat. Bromley Caldari’s design reinvigorated this development with their signature modern timber architecture, carefully oriented for daylight, views, and climate responsiveness

Other notable projects include 144 Ocean Walk

And 470 Ocean Walk

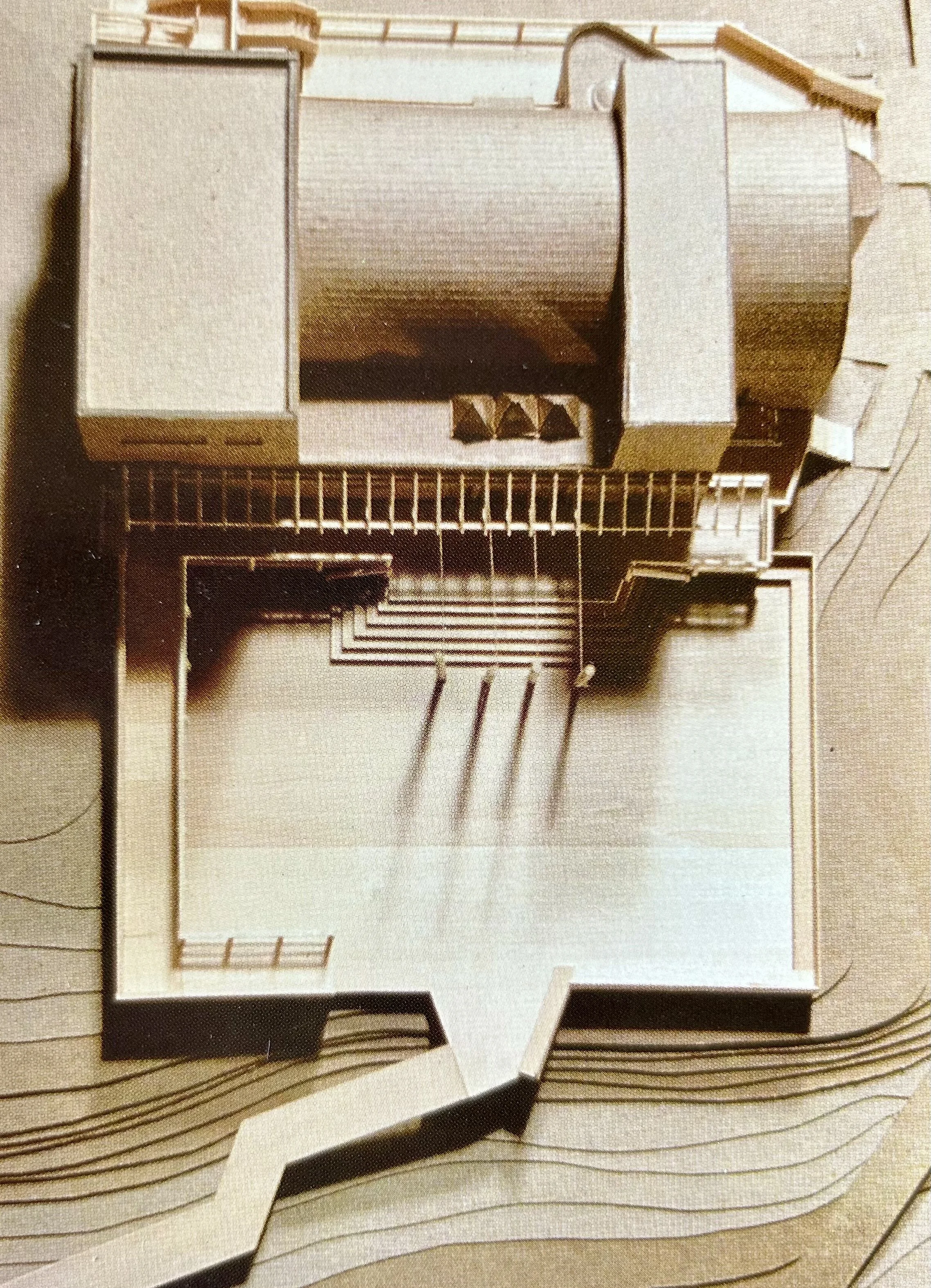

Perhaps Bromley Caldari’s most notable project was the Pines’ 7,500 square foot community center called Whyte Hall. Named after its major benefactor, John Whyte, the Fire Island Pines Property Owners Association (FIPPOA) raised over $3 million to create a place that could support a range of community, artistic and religious activities.

Bromley Caldari beat out three other firms in a competitive bidding process with an innovative design that fitted perfectly with Pines culture and landscape. While the original proposal (shown left) was modified slightly as the project went along, the outcome was nothing less than spectacular.

The multi-functional facility provides both indoor and outdoor space, all designed to maximize light and air, while providing comfort and functionality.

With more than 100 projects the length of Fire Island (and still building), Bromley Caldari Architects has done more to shape the resort’s architectural vernacular than any other. The firm’s projects are stamped with its original ethos and distinct aesthetic. Influenced by Gifford and responsive to the surrounding environment, they also answered the demands of the present. Bromley Caldari beach projects are built using local wood from the northeast of Long Island, and little concrete. Simple orientation and roof angles block the harsh summer sun, allowing the lower sun to penetrate at other times of year. Although air conditioning and heated pools are becoming ubiquitous in the Pines, Bromley himself has never installed air conditioning — the island is always windy, so he just opens windows.

“The idea is a maintenance- free house , made from natural materials,” says Bromley. “You want to arrive, open a beer, put some pasta together, and entertain. You don’t want to have to think about cleaning and packing things away every year. Open the front door and blow—that’s how we do our dusting.”

It should be noted that one of the significant features of the island’s architecture is a less-defined boundary between private and public space. Plots are, for the most part, quite small—65 or 75 feet, by 100 feet long, with lot coverage limited to 35 percent.

“Your neighbors are only 30 feet away, so the length of the houses tend not to have many windows, whereas the front and back are big sheets of glass and overhangs,” says Bromley.

The houses, both old and new, tend to have multiple deck levels, and require cantilevering over bulkheads to maximize outdoor areas. “The outdoor space was always important here, but the indoor space has become important too, in the sense that it’s communal and very seldom separated. It’s all in one big space. It’s all one big bar, for the most part!

Bromley’s success and reputation are such that he is often brought into consult on major projects. After a fire destroyed both the Sip N Twirl and Pavilion buildings in the Pines commercial district, he designed the new Sip N Twirl and consulted on the reconstruction of the Pavilion.

His input to any project remains rooted in his core principles, but adjusted to reflect new demands from a growing population in the twenty first century.

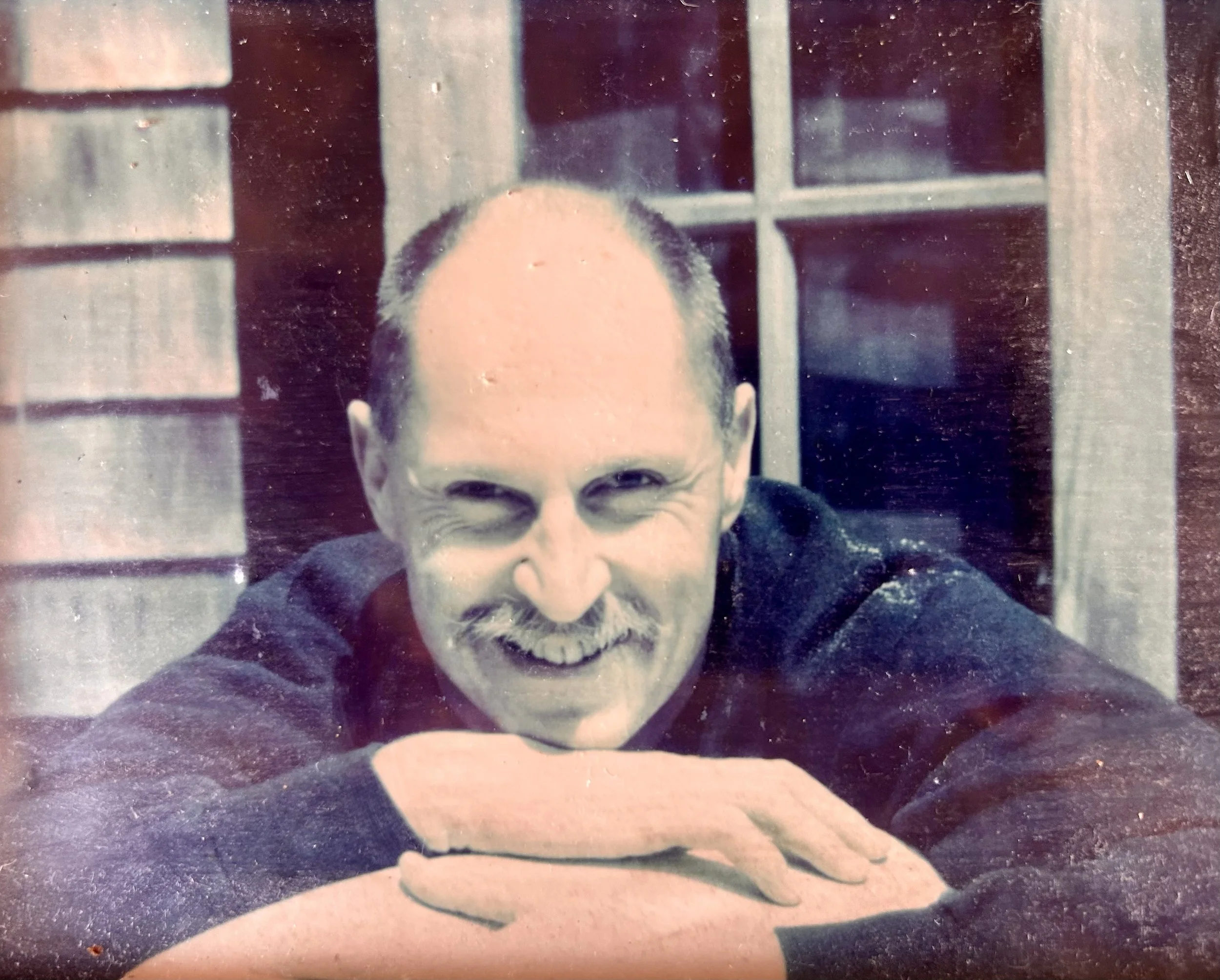

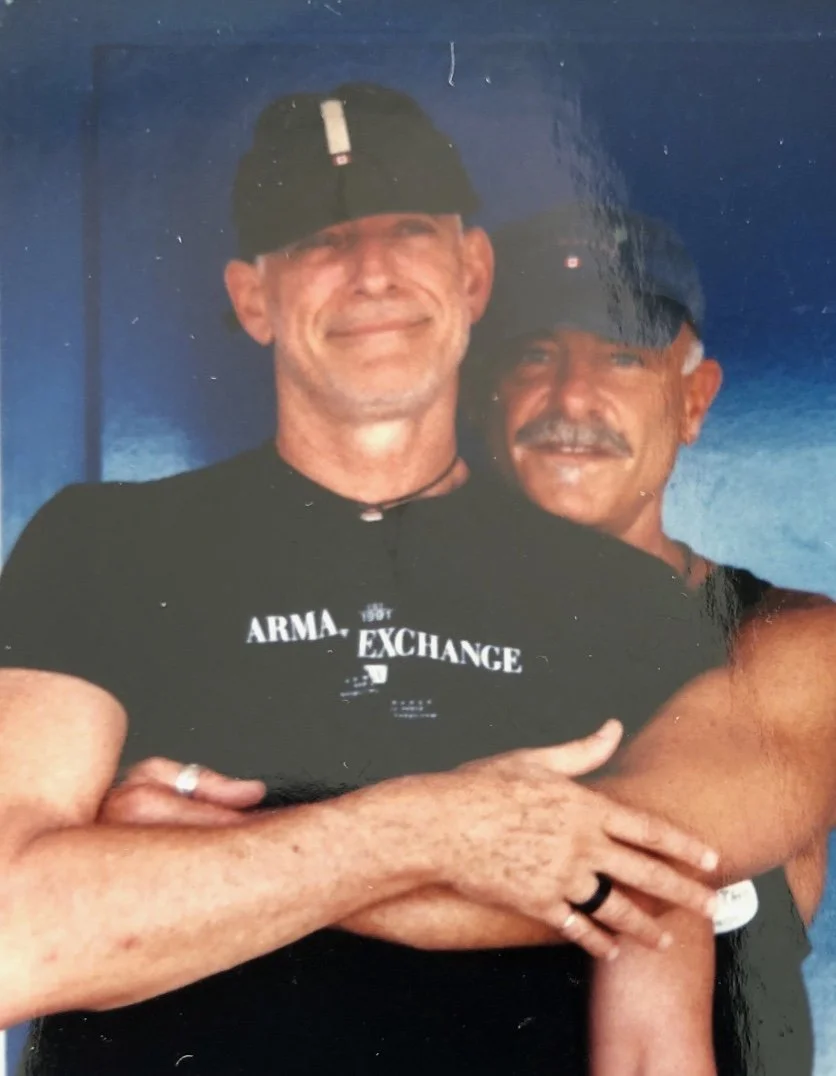

It is impossible to understand Scott Bromley without knowing his husband Tony Impavido. Neighbors in both New York City and Fire Island for decades, the two forged a strong friendship for many years. Tony was in a long term relationship for much of this time, and Scott was also dating other people.

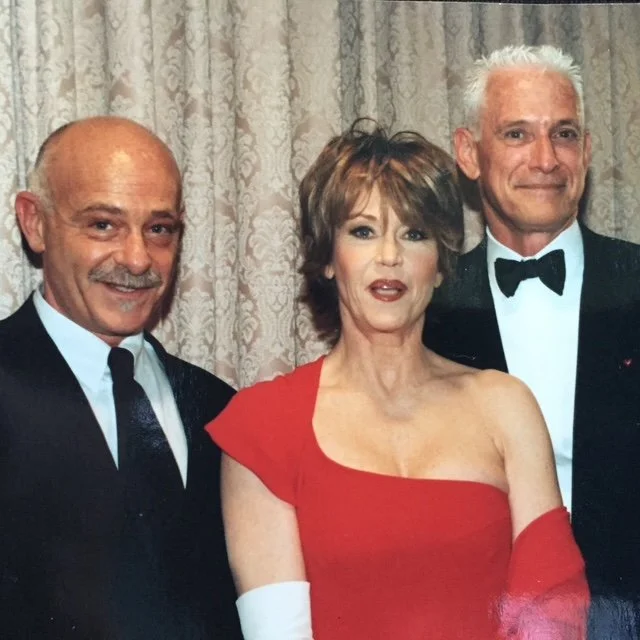

When Impavido’s 25-year relationship ended, Bromley was his sounding board and confidant. Impavido frequently stayed at Bromley’s house and the two forged a strong bond, and built a social network together. Indeed, Impavido, who worked at the New York Film Society for many years often used to show movies for Bromley and other friends at his house on Fishermen’s Path.

Then one January night in 1999, they took their relationship in a different direction. In a manner that could not be misunderstood, Impavido made it clear to Bromley he wanted to be more than friends. The rest, as they say, is history.

As a couple they gelled together quickly and well. In addition to Fire Island, they spent time in New York City, where through Tony’s work with the New York Film Society they mingled with the major stars of the era.

Marriage equality was a long time in coming but Bromley and Impavido were unfazed. In fact, they had no plans to marry, although they did hypothetically discuss it.

Then one summer’s afternoon in 2019, on the ferry en route the Pines, Bromley popped the question, “Will you marry me?”

And before Impavido knew quite what was happening he was in a wedding ceremony orchestrated by Bromley — on the Thursday, 1:30 pm Fire Island Pines ferry! Officiated by the captain and owner of Sayville Ferry Service, Ken Stein, with a full set of passengers bound for the Pines on board. It was an event that is remembered by everyone present.

Bromley and Impavido continue to be very active in the Pines, playing critical roles in the Pines 50th and 60th anniversaries, organizing the first clam bake and continuing to support all charitable and cultural activities in the community. And he continues to design homes up and down the island. They along with their dog Louie continue to live in the same house Bromley purchased back in 1980.

Theirs is a year-round love affair with the Pines, spending Christmas and hosting a New Year’s Eve party every year.

While his architectural genius is well known, today Bromley is just as highly regarded for his warmth, wisdom, charm, wit, and generosity. He is a beloved member of the community, who is always encouraging and supportive to people, offering his insights freely to anyone who asks - often over a perfectly mixed margarita.

In over six decades, he has seen and done a lot, but always looks forward to tomorrow. When asked what he hopes for the future for the Pines, Bromley simply says that it continues to be a place of friendship, support and love.

As an architect, neighbor, friend, event planner, and simply as a warm, loving soul, Scott Bromley’s legacy is etched into the pine groves, boardwalks, and cedar homes that give the Pines its soul. He has left his mark, and the Pines is all the better for it.