Pines Profile - Alice Thorpe (1902-2006)

Educator, Naturalist and Fire Island Pines Pioneer

By Virun Rampersad, July 2025

Alice Thorpe was more than an early settler of Fire Island Pines, she was one of its founding spirits. A fierce champion of nature, outspoken in her pursuit of freedom, and a pioneer in environmental protection, Alice helped shape the Pines into the vibrant, inclusive, and eco-conscious community it is today. Her legacy is woven into its very dunes and pine trees of a community she helped form.

Photo courtesy of Lorraine Gengo

Alice and her husband, John Thorpe, were among the very first to call the Pines home. In the 1930s, long before boardwalks, electricity, regular ferry service and real estate listings, they arrived in the Pines for the first time and joined a group of friends from what was known as the Green Mountain Club. They lived communally on weekends, camping out and sleeping in tents.

Photo courtesy of Lorraine Gengo

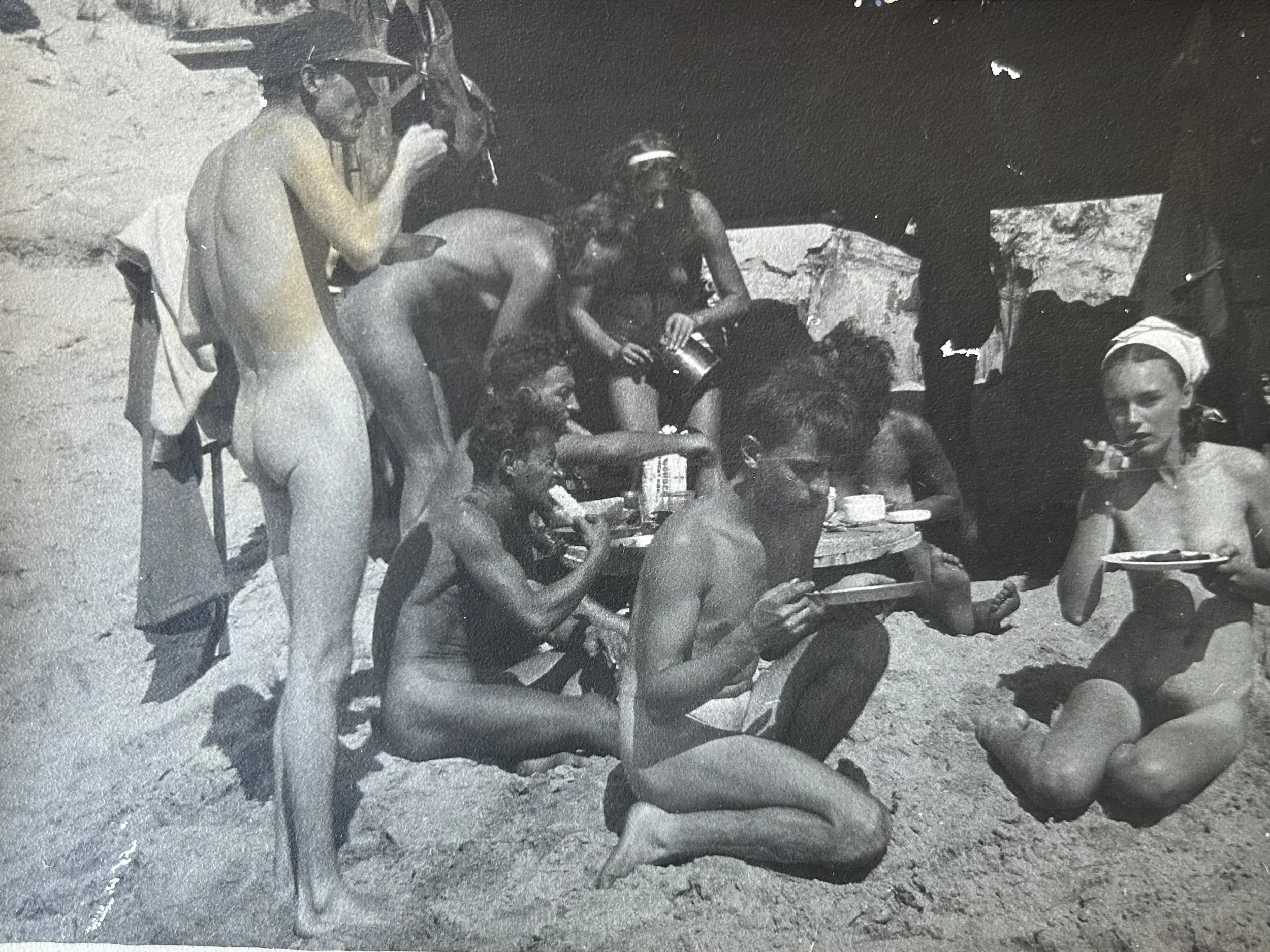

Some of the Green Mountain Club were nudists (or naturalists, as Alice preferred) and introduced her to that lifestyle. Together, they enjoyed the tranquil, natural, unspoiled surroundings of the beach and its environs.

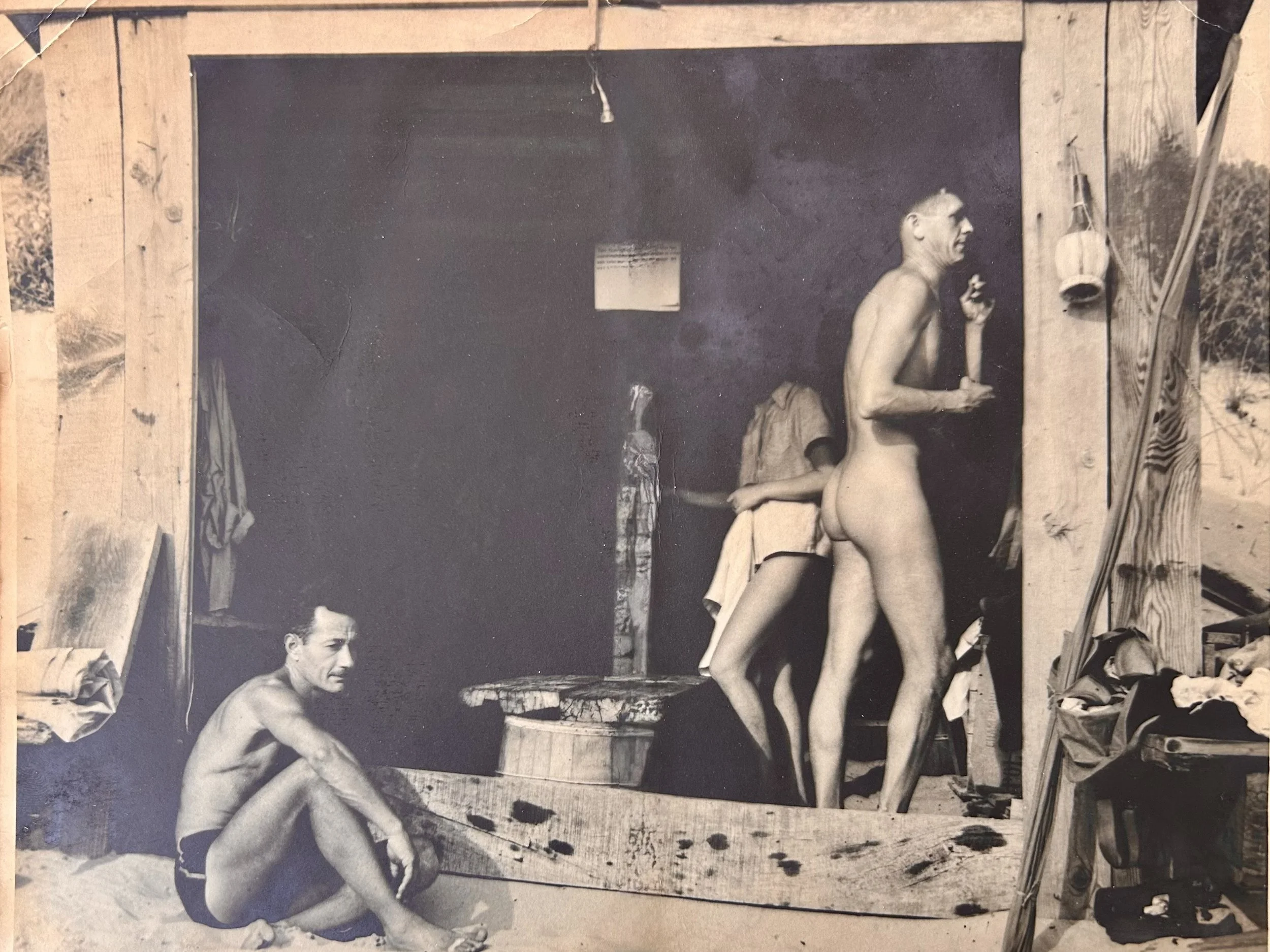

Early Green Mountaineers. Photo courtesy of Lorraine Gengo

After years of living in tents, a few women from the group went over to the bay side of Fire Island and fetched debris from the 1938 hurricane to build lean-tos and huts.

One of the Green Mountain Club’s first huts. Photo courtesy of Lorraine Gengo

They embraced a life of simplicity and joy—nude, sun-kissed, free. Their makeshift cabins, affectionately named “Slap Happy” and “The Black Hole of Calcutta,” weren’t just shelters—they were symbols of a bohemian dream, alive with laughter, music, and community.

Green Mountain Club. Photo courtesy of Lorraine Gengo

Photo courtesy of Lorraine Gengo

Photo courtesy of Lorraine Gengo

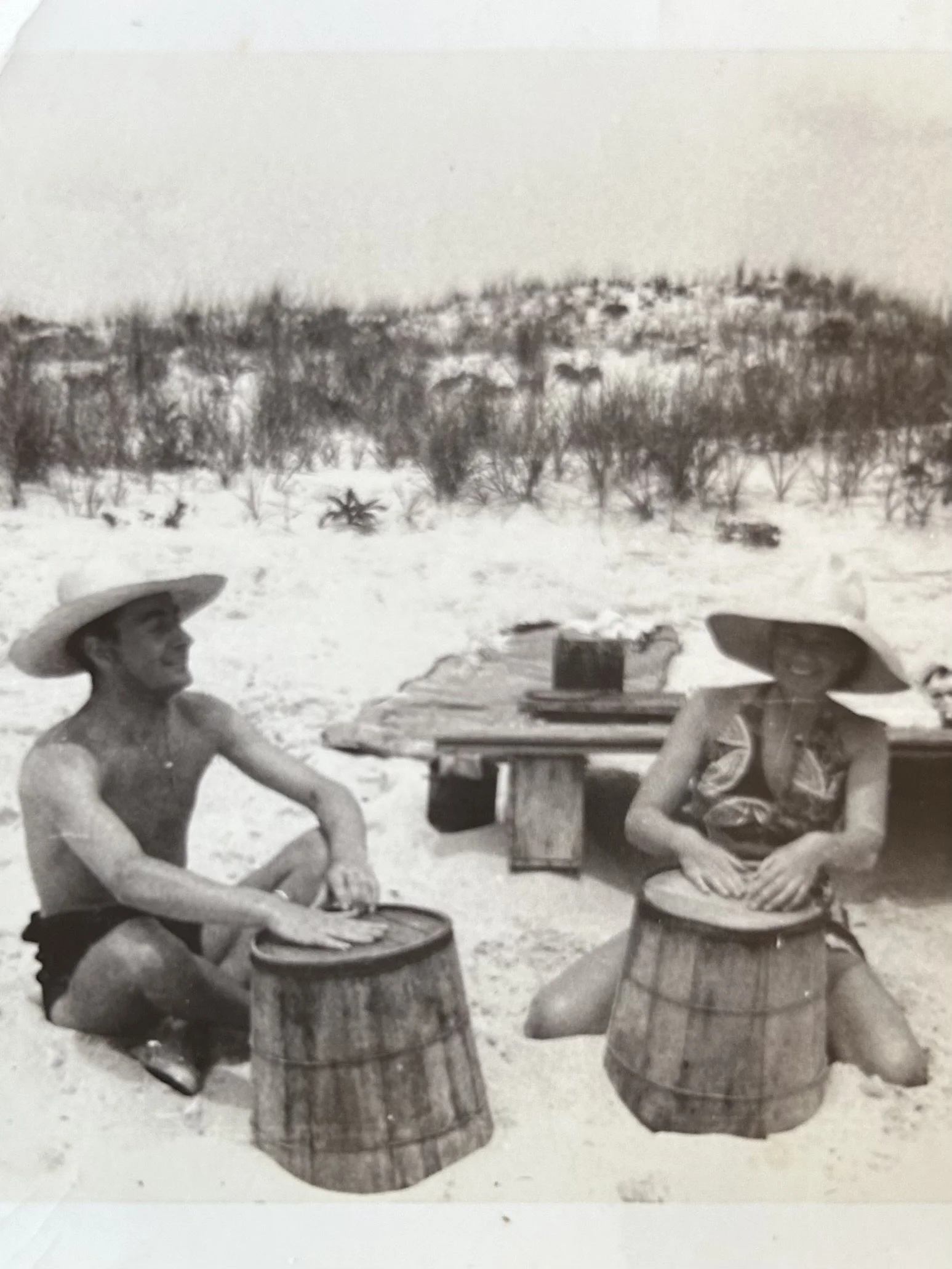

A dedicated English teacher at George Washington High School in Manhattan, Alice brought her intellect and values to everything she touched. She was sharp-witted, fiercely independent, and utterly devoted to the natural world. Summers on Fire Island were her favorite time. Whether strolling on the beach or skinny-dipping in the ocean, Alice moved through nature not as an observer, but as a part of it. She gardened with reverence for native species, always carrying a screwdriver to salvage hardware from washed-up debris. Nothing was wasted. Everything was sacred. At the end of each season she and her group would bury their belongings in barrels and return to claim them at the start of the next.

The barrels used to store belongings over the winter. Photo courtesy of Lorraine Gengo

In 1947, John, an Army veteran and Con Edison engineer, secured surplus Army housing units. He, along with Alice and their family, hauled them across the bay by barge and then by draft horses across the dunes. Together, they built one of what was essentially the Pines’ first permanent homes with their own hands. Alice learned to paint, shingle, varnish, and plant—all while raising nieces and nephews and looking after friends’ children. In so doing, they didn’t just build a house; they put down roots and built a future.

In 1952 the Home Guardian Company, which had purchased the land in the 1940s, renamed the community Fire Island Pines and began selling off lots for development into a new beach community. Undeterred, Alice and John bought property their house was sitting on (they had technically been squatting before) and became key figures in the new community.

Photo courtesy of Lorraine Gengo

This home, in the newly christened Pines, was on a high dune on what is now known as Ocean Walk, between Shell and Sunburst Walks, and remains in the family today.

The Thorpes and their family bought several lots, creating a compound that included houses for John and Alice, and her brother Carl and his wife, Mabel. They also dedicated space to preservation, which allowed them to retain a semblance of the privacy and solitude they had previously enjoyed.

Photo courtesy of Lorraine Gengo

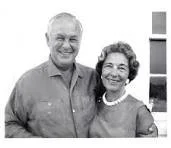

As the community began to take root, Warren Smadbeck, who owned the Home Guardian Company, engaged his son-in-law, Ted Taussig, and his wife Doris to sell lots to family and friends.

Ted and Doris Taussig. Photo courtesy of Doris Taussig.

Around this time, the Pines had begun attracting members of the gay community who were seeking an alternative to Cherry Grove. Alarmed by this growing presence and fearing it would depress property values, a homophobic group of homeowners badgered Taussig and the Home Guardian Company into launching a campaign to purge the area of what was referred to as “this cancer.” These efforts reached a peak in the late 50s when it was proposed that the community introduce a questionnaire for potential renters and home buyers. This questionnaire was very intrusive, seeking information on their personal lives, including their religion, their politics, their families, and even contact information for their employers.

For Alice this was a bridge too far. At a pivotal community meeting, she stood and delivered a passionate speech so powerful it is still remembered as a turning point in the anti-gay hostilities. Certainly there is no evidence that the questionnaire was ever introduced.

Alice and John Thorpe. Photo courtesy of Lorraine Gengo

After residents of Cherry Grove came to help fight the devastating 1959 Memorial Day fire in the Pines’ commercial district, much of the hostility toward the LGBTQ+ community began to fade. Over time, more gay people began renting and purchasing homes, gradually growing in both number and acceptance. Alice was quietly supportive of a friend (believed to be Mrs. Stowell) who was helping gay people acquire property, though she was not active in doing so herself. Later, through her involvement in community theater and her friendship with her neighbor Gil Parker, she became more aware of the challenges gay people faced, which led to greater understanding, empathy and embrace. As she remarked, there were as many gay people in the community who were as much friends to her as the straight ones.

Alice’s main social cause was protection and preservation of the environment. She frequently clashed with developers Warren and Arthur Smadbeck, owners of the Home Guardian Company. Alongside John, Carl, and Mabel, she protested their aggressive development efforts, including the bulldozing of dunes, the cutting of trees, and the dredging of the harbor. Initially she was not successful. The Pines Harbor was dredged; trees were cut down and homes and boardwalks were constructed. Before her eyes, the place she loved was “torn apart” in the name of development. Terrified it would become like other parts of the East Coast she bought parcels of land not to build, but to save.

In the early 60s a great opportunity came when President Lyndon B. Johnson considered designating Fire Island a national seashore. Alice seized it. She personally guided Johnson’s representative through the Pines, and spent an entire day making sure he understood what would be lost if developers had their way.

President Lyndon Johnson. Stock Photo.

Thanks in part to her efforts, Fire Island was declared a National Seashore in 1964. This was a game-changing moment. The designation halted expansion and froze Fire Island’s footprint. No further development was permitted, meaning existing communities could not grow, and undeveloped tracts, like the land between the Pines and Water Island, as well as the beloved “Meat Rack” between the Pines and Cherry Grove, were preserved. It was a major victory for Alice and others who had the foresight and courage to stand up to powerful developers in defense of the environment. Their efforts shaped not only the future of the Pines, but of Fire Island as a whole.

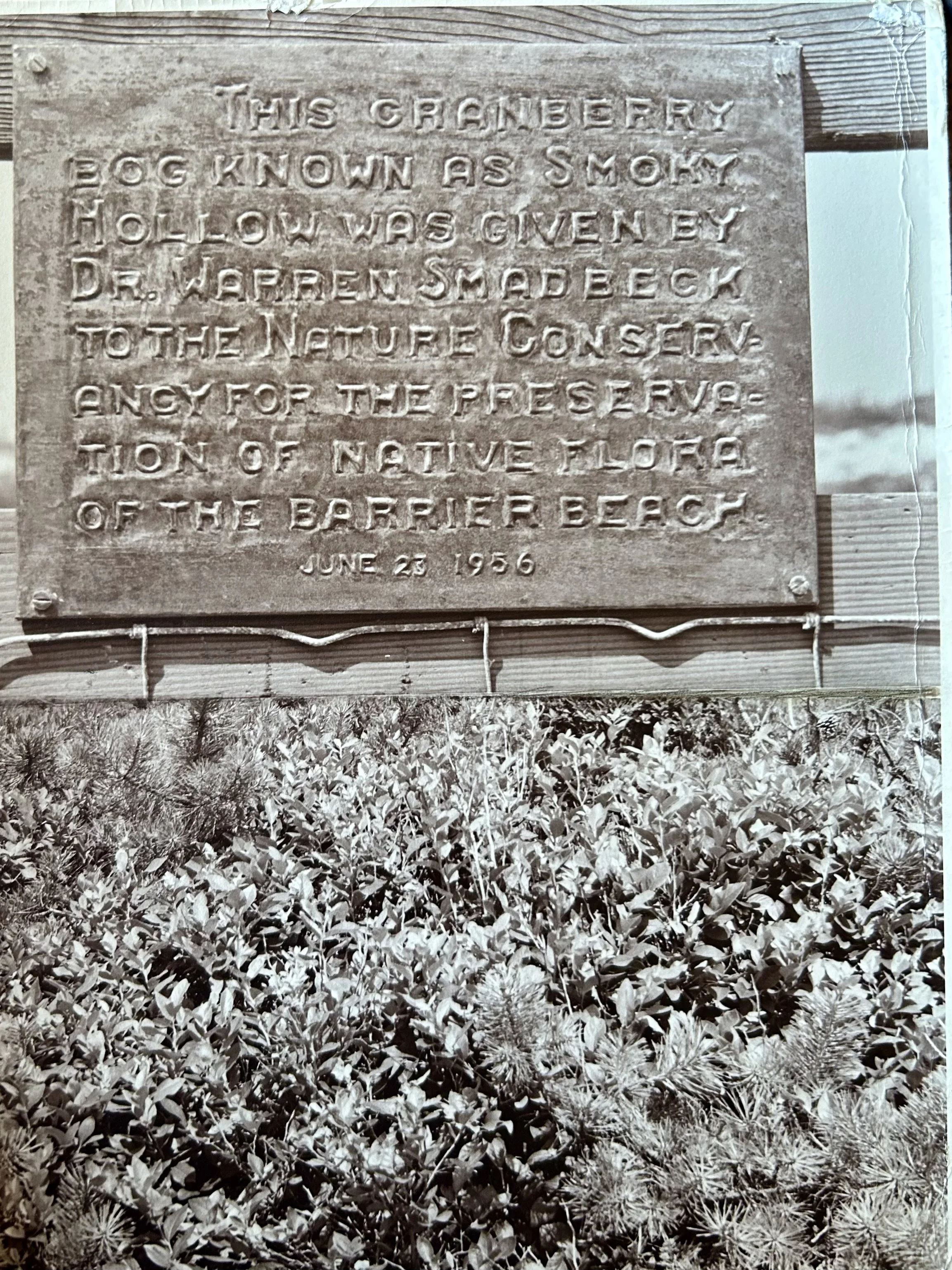

One of her proudest accomplishments in the Pines was saving a native cranberry bog, now known as Smokey Hollow. In 1956, a dedication ceremony honored her efforts by naming Alice its official guardian. A commemorative bronze plaque was installed to mark the occasion, remaining in place until the 1970s.

Photo courtesy of Lorraine Gengo

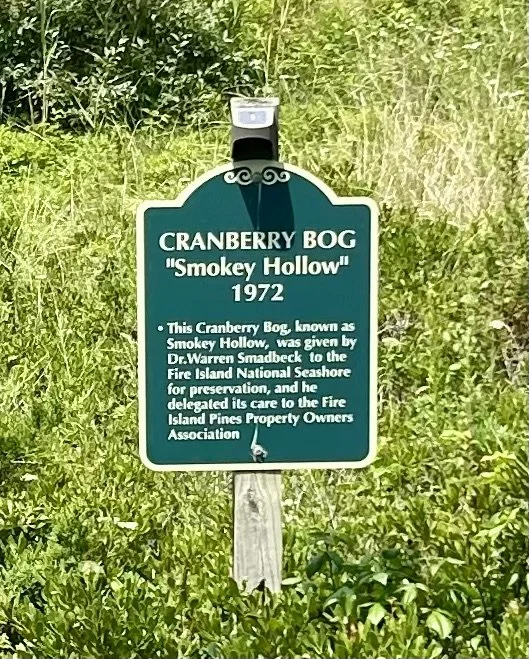

Alice and John were able to convince Warren Smadbeck to donate the land to the Fire Island National Seashore and delegate care to the FIPPOA.

Cranberry Bog Sign in 2025. Photo courtesy of Virun Rampersad

For more than eight decades Alice spent some time in the Pines every summer, continuing to visit long after John passed.

Alice and John Thorpe. Photo courtesy of Lorraine Gengo

She passed her love for the place down through her family, infusing the next generations with the same sense of wonder, stewardship, and justice. Not surprisingly her descendants continue to spend time at her house every summer.

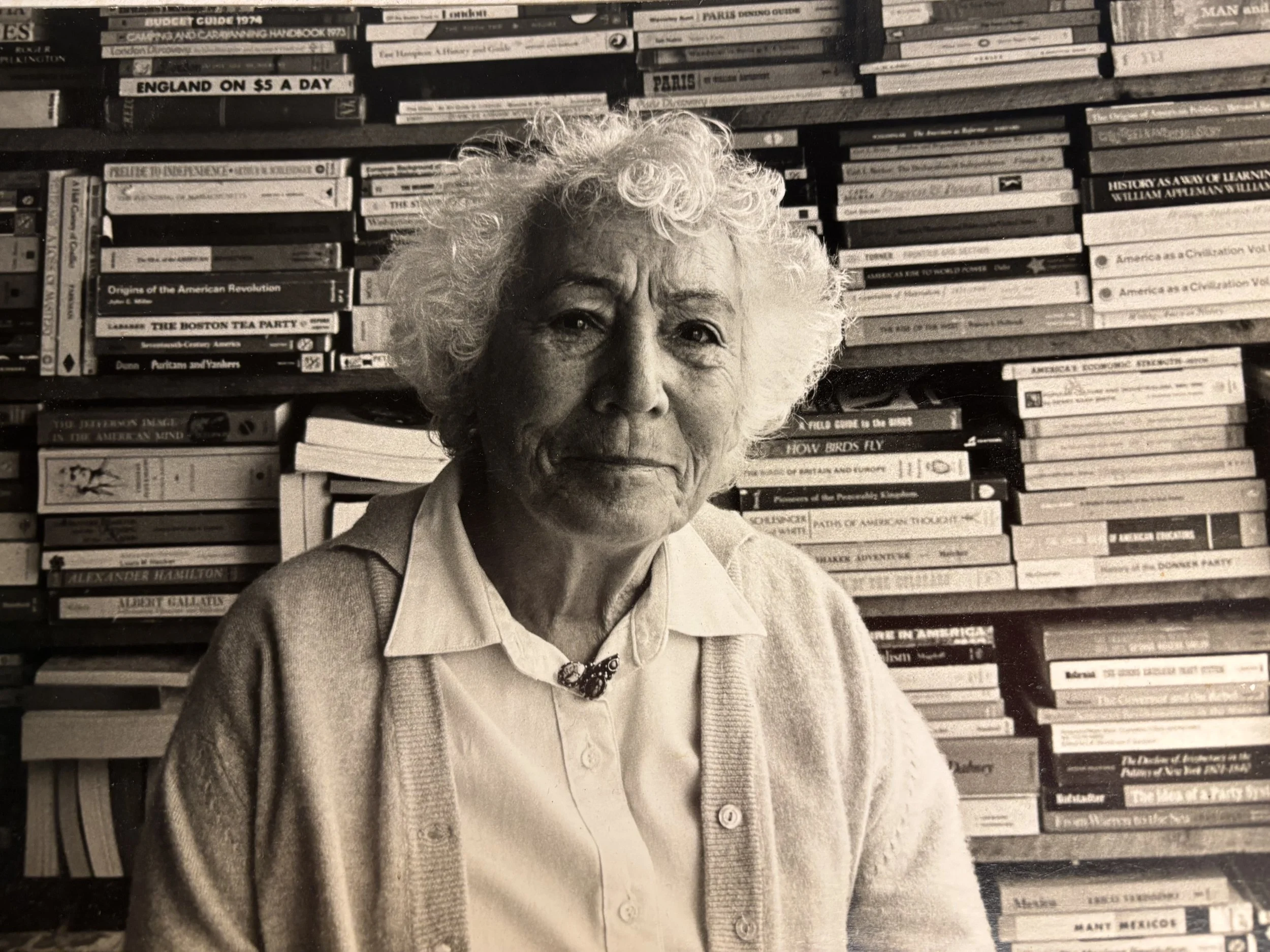

Photo courtesy by Sylvan Cole

Photo courtesy of Lorraine Gengo

Alice died in 2006 at the age of 104. Her ashes were scattered in the Pines, a final act of belonging in the place she cherished most.

In her lifetime, Alice Thorpe came to embody the values the Pines holds dear: freedom, tolerance, respect, and responsibility. She didn’t just believe in those ideals, she lived them, fought for them, and helped make them real. And time proved her right. Far from depressing property values, the now predominantly gay Pines commands a premium over nearly every other Fire Island community and has become a leader in environmental protection and preservation. Moreover, it remains a place where everyone, regardless of race, gender, national origin or sexual orientation, is welcome and can be their authentic selves, clothed or unclothed. This is Alice’s enduring legacy in the place she called home.